Some Keys and Proposals to Rediscover a Judeo-Christian Imaginal and Open to Research in the Footsteps of Marcel Jousse1.

The approach and reading of biblical texts, even today, often remain practiced in a purely intellectual mode. Small groups, frequently monastic, work by associating moments of meditation with their exegetical practice. The most commonly used technique today in Christian circles is the lectio Divina, a method inherited from the Jewish mystical tradition of PaRdéS2. This approach was interpreted and adapted by the fathers of the Christian Church and various doctors of the faith, such as Saint Benedict of Nursia, the patriarch of Western monks. However, this remains quite limited compared to the treasures offered by the mystical practices of Eastern Christians and, above all, those of the Hebrew tradition.

These latter disciplines and practices require some knowledge of sacred Hebrew to be meaningful. Their primary and ancient sources are found in an extensive body of literature known as the mysticism of the Celestial Chariot (Merkabah3 / מְֶרכָָּבה) and the Palace (Sifrout ha-Heikhalot / ספרות ההיכלות), developed in the wake of the Book of Ezekiel. This literature has been interpreted by numerous sages—Jewish, Christian, and Muslim alike. As a result, the techniques and disciplines abound, ranging from the simplest to the most complex, offering a powerful encounter with the Source of all life through the intercession of the Holy Spirit (ruach ha-kodesh / רוח הקודש).

In the footsteps of various 20th-century rabbis, such as Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan4, the compilations of texts by Marc Alain Ouaknin, and the miraculously rediscovered writings of Rabbi Kalonymus Schapiro5 (1889–1943) from the Warsaw Ghetto, the practices and mysticism of Jewish traditions have been revealed to a broader audience, with older texts translated and republished. The cultural enrichment that anyone can draw from this is thus increasingly accessible. However, this is only truly effective if one acquires some knowledge of biblical Hebrew. Without it, the « seeker » will miss the essential: the constant interplay between intellectuality and contemplation. This back-and-forth sows seeds, with each feeding the other—intellectuality leading back to contemplation, and vice versa. Without some biblical Hebrew, it is impossible to access the « deep meaning » encountered in lived contemplation. Using Hebrew without understanding it risks locking oneself into practices akin to occultism or idolatry.

Moreover, the learning of sacred Hebrew should not be undertaken solely in the « modern mode » of university teachings, as is generally practiced today. These rely on pedagogical methods modeled after the teaching of other vernacular languages. Sacred Hebrew is not the language of a nation; it aims to edify the mystical Israel. It is a living language dedicated to the encounter with God. That said, one should not oppose the methods—traditional mystical pedagogy and modern pedagogy—for they are necessarily complementary. The sages of Israel, along with many doctors of the Christian faith, have emphasized that the linguistic rules of biblical Hebrew safeguard the proper understanding of the divine message6. Nevertheless, the modern university teaching of biblical Hebrew, while rich in its semiological exploration of vocabulary, does not foster in the learner the relationship with God intrinsic to sacred Hebrew—a relationship brought to life through the exercises of traditional Jewish mystical practices, particularly those of the PaRdéS mentioned earlier. To explore these exercises, working with Hebrew vowels offers a marvelous gateway, a wonderful first approach to the powerful techniques that coherently open to the Judeo-Christian theophany and, in particular, to a profound understanding of the sacred texts foundational to our civilizations.

It is worth noting that Kabbalah has crystallized the main mystical practices into synthetic techniques, which are particularly effective disciplines. We will delve into this in greater detail later. Similarly, these Kabbalistic techniques influenced numerous Catholic Christian mystics from the Renaissance7 onward. This is beginning to be recognized and accepted beyond a few specialist circles. The indiscriminate anathemas launched against these Kabbalistic techniques and traditional Jewish practices were too often the work of ignorants or pseudo-scholars—true fanatics driven by an irrational fear of seeing Christian work abandoned in favor of Judaism. In this stance, these censors primarily demonstrated their lack of faith and their shortcomings.

Moreover, one cannot ignore the influence of ancient and traditional Jewish mystical techniques and practices on similar practices of the « Desert Fathers » (3rd and 4th centuries), the Philokalia, and hesychasm. For example, the technique of folding over the navel, taught notably by Symeon the New Theologian (born in 949, died March 12, 1022), is directly linked to the « prophetic posture » (head between the legs), known as that of the prophet Elijah, practiced by Jewish mystics and developed in the Talmud8. Finally, let us not forget that « the call of the desert »—a withdrawal from the world to attach oneself to God, a movement of being where one experiences mystical practices and techniques in singularity and in communion with peers—is an utterly transversal theme, rich with millennia of sharing across monotheistic religions.

From Meditative Vocalization to Text Interpretation

The vocalization of biblical Hebrew vowels and the exercises derived from them are part of the traditional disciplines of Jewish mysticism and Kabbalah. For those who speak Hebrew, these potentially open a powerful understanding of the texts. Christians, too, can practice these exercises with benefit. Through the chant of Hebrew vowels, the body is engaged in a proper invitation to receive the gifts of what our Judeo-Christian traditions call the Holy Spirit, in Hebrew ru’aḥ ha-qodesh (רוח הקודש). This is reminiscent of the nine ways of prayer through the body of Saint Dominic9. The practice of vocalization and the chant of Hebrew vowels offer various approaches. The most essential aims to make the vowels (O, A, E/È/É, I, OU) resonate (vibrate) at different points in the torso and head. Under the influence of Abraham ben Samuel Aboulafia (born in 1240, died probably shortly after 1291), the chant of vowels was associated with various head movements10

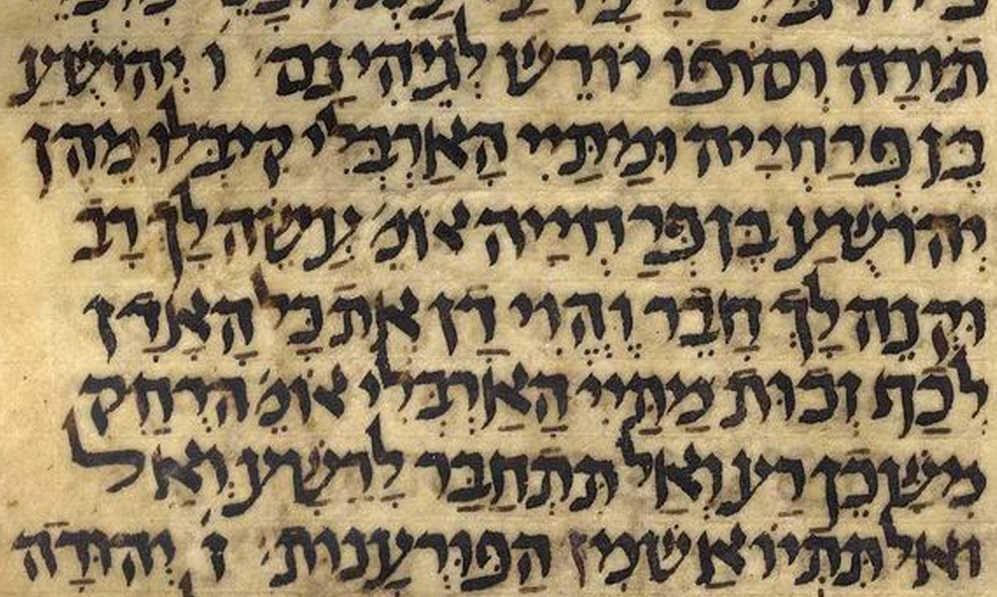

To understand the mystagogical, philological, and traditional value of the five main vowels of sacred Hebrew, it is helpful to review some basic linguistic elements. In biblical Hebrew, before the Masoretes, vowels were not written. It was the Masoretes who instituted signs to ensure that the pronunciation of biblical texts remained consistent throughout the diaspora. The vowels of Hebrew, like those of all so-called Semitic languages, had to be imagined for reading—an exercise in deciphering the meaning of each word, deduced from the potential and broader meaning of the sentence. It is thus about thinking the invisible through the visible. In Semitic languages, and particularly in the sacred texts of the Torah scrolls displayed in synagogues, vowels have always had this imaginative, mystagogical function, linked to the invisible—the divine—residing beyond creation.

Before the Masoretes10, the learning of vowels was primarily through oral teaching passed down by mothers to their children. Often through chants and melodies aimed at soothing their child from intrauterine life11, mothers were the first initiators. These traditions, which long survived in the Western Maghreb, remain poorly studied even today.

The 22 consonants of Hebrew belong to the visible and the temporal. In the perspective of Hebrew cosmogony, while they structure our universe as the origin of creation12, they are truly invested with meaning and divine power only through the vowels, which pertain to the divine breath (Holy Spirit) and thus to the invisible. The divine breath gave birth to the 22 letters, through which the universe was created. Expressed through the vowels, the divine breath orders the 22 consonants that compose creation. Vowels—invisible, ineffable, eternal—animate the visible within the temporal, serving as a mirror in which humankind can perceive its Creator.

In Semitic languages, vowels, being unwritten, form a sonorous, vibratory, and fluidic bridge, revealing the immaterial within the material. In this mystical vision, the sound of vowels structures matter. Vowels are the tools of the theophany of language, with the power to reveal the deep meaning of each thing, making perceptible the divine presence residing within it. According to Kabbalah, it is the vowels that reveal the name of God in every particle of creation. For example, verse 115 of the Bahir13 states:

"And the circle14, what does it designate? It is the vowel points of the Torah of Moses, all of which have a circular form; they fulfill, in the consonants, a function similar to that of the soul in the human body, which ceases to live as soon as the soul leaves it and which cannot accomplish any act, great or small, without the soul vibrating within it. It is the same with the vowel. One cannot pronounce any word, great or small, without resorting to the vowel."This theophany and philology of vowels, rooted in the linguistics of sacred Hebrew, have also been extensively developed in the texts of the Zohar. The first to transmit a written mystical recitative practice related to this was Rabbi Abraham Aboulafia (mentioned earlier), primarily in his text Light of the Intellect15. In chapters 27, 28, and 29, he proposes various techniques to « rotate » the vowels on divine names.

The science of vowels and their chant on pentatonic scales is also a shared treasure of the universal heritage of Levantine cultures. Various modern anthropological studies on the theophanies of monotheistic traditions have highlighted principles recognizable in the mystical practice of chanting Semitic vowels. In my view, the vocal practices of ancient oral teachings of vowels belong to pedagogical and initiatory practices that enhance and complement those integrated into the renowned « Anthropology of Gesture » framework established by the Jesuit priest and anthropologist Marcel Jousse16. The recitation of vowels—unverbalized onomatopoeias—perfectly aligns with the « mimism17 » practices conceptualized by the anthropologist. A precise inventory of this remains to be done.

Furthermore, these pedagogical practices, part of the « Anthropology of Gesture » and enriched by Jewish mystical practices related to vowels, offer a potential Judeo-Christian resourcing of the Imago Templi, a concept primarily developed by Henry Corbin18 from the Sufi practices of Iranian Shiism. Corbin’s focus on Islam does not allow seekers rooted in Judeo-Christian cultural frameworks to access the practices of their own civilizational movement. The omission or underrepresentation of Kabbalistic sources in the concept of the Imaginal, from which Corbin’s Imago Templi emerges, has sparked significant scientific debate about the comprehensiveness of the mystical elements considered. It should be noted that this brilliant 20th-century thinker developed the concept of the Imaginal19 at a time when many elements of Jewish mystical traditions were poorly known in Europe, and in French academic circles, much of Christian mysticism was sidelined. These barriers are beginning to lift today, and many treasures are being made available to a wider audience20.

Traditionally, in biblical Hebrew—as still practiced today with the Torah scrolls used ritually in synagogues—and even in reading modern Hebrew, vowels must be « imagined » by the reader for comprehension and, especially, for aloud pronunciation of texts. This requires constant mental gymnastics from the Hebrew speaker, a process made easier when learned in childhood. Here, the technique of chanting vowels, which involves making them resonate in the body, proves an excellent aid for approaching biblical Hebrew as an adult.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it seems valuable to dwell on a Talmudic teaching that particularly emphasizes the chant of vowels as a tool for exploring the deep meaning of texts. Specifically, this concerns verse III of chapter I of the Song of Songs:

"Your perfumes are sweet to breathe; an aromatic oil that spreads, such is your name. That is why the young girls love you."

In Hebrew:

לְרֵיחַ שְׁמָנֶיךָ טוֹבִים, שֶׁמֶן תּוּרַק שְׁמֶךָ; עַל-כֵּן, עֲלָמוֹת אֲהֵבוּךָThe Babylonian Talmud21, in its treatise Avodah Zarah at XXXV/b, proposes a practical exercise of interpretation of this verse through the « Tserouf » (permutation) of vowels. Here is a translation (elements in parentheses are my additions for clarity):

Rav Nahman, son of Rav Ḥisda, proposed a homiletic reading of a verse: "What is the meaning of what is written (Song of Songs 1:3): Your perfumes are sweet to breathe; an aromatic oil that spreads, such is your name. That is why the young girls love you. It is a metaphor evoking a scholar of the Torah. To what is a scholar of the Torah comparable? To a flask of pelatine (precious oil with sacred properties). When he transmits his knowledge, his perfume diffuses; when he withdraws from the world, his perfume does not diffuse.

The Gemara (Perfect Study) notes: Moreover, when the scholar of the Torah diffuses his knowledge, secrets he was unaware of are revealed to him. It is said: ‘The young girls (alamot / עֲלָמוֹת) love you’ (Song of Songs 1:3), and one can read the word alamot differently (with other vowels), yielding aloumoth (secrets). Thus, the verse says: Secrets love you. Furthermore, one can read: (you, the scholar of the Torah) the angel of death loves you. For if the word alamot (the young girls) is read differently (with other vowels), it becomes al mavêt (עַל מָוֶת / angel of death). Then the verse says: The angel of death loves you. Additionally, one can understand that the scholar of the Torah inherits both worlds—one is the present world (temporal), and the other is the World to Come (eternal)—for one can pronounce alamot (the young girls) differently (with yet other vowels), yielding olamoth (the worlds). Thus, the verse can be read: The worlds love you."By inviting us to pronounce the word « young girls » (Hâlamoth / עֲלָמוֹת) with vowels different from those of the Masoretic text, the Talmud enables a spiritual deepening that serves as a teaching. It is worth pausing here to appreciate the richness of the vowel-chanting exercise at work.

First permutation: It suggests reading Hâloumoth (עֲלוּמוֹת) by replacing the "a" of the consonant lamed (ל) with an "ou" (written וּ). This implies that the scholar of sacred texts discovers new knowledge when sharing it. This is profoundly true: when we articulate what we know for someone else, striving to be understood, we integrate what we perceive from the other. Inevitably, we do more than formulate—we reformulate. In this act of reformulation to make things accessible, something new often emerges. Moreover, what is transmitted and deeply heard by the other produces an understanding shaped by their own uniqueness, surpassing what was initially said.

Second permutation: In this perspective of increasing understanding through sharing sacred texts, the subsequent vowel permutations find their full explanation. By enhancing our understanding of God through shared comprehension of sacred texts, we amplify God’s presence; our souls expand with immortality. This is how "the angel of death loves us," for what is mortal in us diminishes (al mavêt = עַל מָוֶת / angel of death).

Final permutation: We place an "o" on the consonant ayin (ע) in "young girls" (Hâlamoth / עֲלָמוֹת) instead of an "a," yielding Holâmoth (עוֹלָמוֹת), allowing us to read "the worlds love you." Indeed, in the biblical sense, by increasing the Immortal within us, our glory in God grows in the other world—that of eternity. Through this, we fulfill our earthly mission. By exercising our free will, we realize the hope placed in every human life by divine mercy. Thus, the temporal world and the eternal world love us.- Marcel Jousse is a researcher in anthropology and linguistics. He was born on July 28, 1886 in Beaumont-sur-Sarthe and died on August 14, 1961 in Fresnay-sur-Sarthe. Ordained a priest in 1912, he joined the Society of Jesus in 1913. A student of Marcel Mauss, Pierre Janet, Georges Dumas, and Jean-Pierre Rousselot, he mingled with the greatest scholars of his time who recognized in him an exceptionally gifted researcher. ↩︎

- The Pardès (פרדס) is an acrostic of Jewish biblical exegesis. It refers to the four traditional exegetical approaches of rabbinic Judaism, the 4 levels of possible interpretations in the study of the Torah. This acrostic is composed of the initial letters of these different approaches:

Pshat (פְּשָׁט), literal

Remez (רֶמֶז), allegorical

Drash (דְּרַשׁ), homiletic

Sod (סוֹד), mystical

In the tradition of Kabbalah and the Talmud, the PaRDeS resembles the word « paradise »; the « Pardès » designates the Garden of Eden, a place of divine presence where the student of the Bible can attain perfect beatitude and an almost complete understanding of God. ↩︎ - The main texts dealing with the mysticism of the Merkabah, that is, the vision of the heavenly throne and the divine chariot, date from the 5th and 6th centuries. This literature seems to have its sources in Hebrew oral traditions that may date back several centuries BCE. The texts of the Merkabah literature were imported to Europe from the study centers of Babylonia via Greece, Italy, and Germany, and they have been preserved in manuscripts dating from the late Middle Ages. These texts have strongly influenced Christian theology. Most are called the « Book of Hekhalot » (Book of Palaces) and contain descriptions of the palaces and the trials that the mystic undergoes in his journey to the divine throne. Christian mystics from the East, such as Saint John Climacus (born around 579, died around 649) and from the West like Saint Teresa of Avila (born March 28, 1515, in Gotarrendura in Old Castile and died October 4, 1582, in Alba de Tormes) refer to them. The main Jewish figures in this literature are the Tannaim Yohanan ben Zakkai, Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanos, Rabbi Akiva, Ishmael ben Elisha the High Priest (the grandfather of the Tanna Rabbi Ishmael), and Nehuniah ben ha-Kanah (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 80b). In his Guide for the Perplexed, Maimonides identifies the Ma’asé mercabâ with what he considers the highest of sciences, metaphysics, as leading to the knowledge of God. ↩︎

- Aryeh Kaplan, born on October 23, 1934, in the Bronx, New York, and died on January 28, 1983, in Brooklyn in the same city, was an American Orthodox rabbi, as well as a thinker and author of more than fifty books related to Judaism. From his essays on the Torah, the Talmud, and Kabbalah to his publications on the philosophy of Judaism, he is one of the important figures of the baal teshuva movement. His scientific training had earned him the title of « the most promising young physicist in the United States. » ↩︎

- Rabbi Kalonymus Shapiro (1889-1943) is an important figure in Hasidism and in the spiritual resistance to the genocide perpetrated by Nazi Germany. Kalonymus Shapiro was a rabbi in the Warsaw ghetto, and his texts, preserved in the earth, were found written in an attempt to find meaning in the face of this inconceivable ordeal; as well as an exposition of meditation and contemplation techniques inspired by the Kabbalah. The original editions of Rabbi Kalonymus Shapiro’s texts were published in Hebrew, Ech Qodech (The Holy Fire) in 1960, and Bnéi Machavah Tova (Children of a Good Thought) in 1989. Several translations have appeared in English. Rabbi Shapiro, also known as the Piaseczner Rebbe of the Warsaw ghetto, notably initiated the meditation technique called Hashkata (the ‘calm’), inviting us to observe our thoughts in a process integrating breathing in ‘three times’. A true anticipation of Mindfulness Meditation, the rebbe invites us to cultivate within ourselves, through the repetition of chosen words, the qualities we wish to embody. His texts are rich in implications that open up various practices of pronouncing divine names. ↩︎

- I invite you to read on my site: https://lun-deux.fr/, the text I wrote summarizing this same idea 6: The linguistics of biblical Hebrew, a crucial field for the proper theological understanding of the texts.

↩︎ - *To historically mark this assertion, I invite the reader to take note, at least, of two things. The first is the impressive work done by Professor Chaim Wirszubski (1915-1977) and published by Éditions de L’ÉCLAT, under the title: Pico della Mirandola and the Kabbalah. This book also contains the article by Professor Gershom Scholem (1897-1982): Considerations on the history of the beginnings of Christian Kabbalah. The second involves studying the life of a character who is David Drach, son-in-law of the Chief Rabbi of France (Emmanuel Deutz), who became the knight Paul-Louis-Bernard Drach (born March 6, 1791, in Strasbourg and died in January 1865 in Rome). A former French rabbi of Alsatian origin, Kabbalist, converted to Catholicism, he was a librarian of the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith in Rome. ↩︎

- On this subject, I invite you to read « The Head Between the Knees. » Contribution to the study of a meditative posture in Jewish and Islamic mysticism, by Prof. Paul B. Fenton in the Review of Religious History and Philosophy, Vol.72, 1992/4 p. 413 to 426. ↩︎

- I invite you to discover on this subject, the book by Sister Catherine Aubin (Dominican): Pray with her body, in the manner of Saint Dominic, published by CERF. ↩︎

- Having practiced this technique for many years, I invite those who would like to approach this practically to contact me (bruno.fou32@gmail.com). ↩︎

- The Masoretes (Hebrew בעלי המסורה ba’alei hamassora, « masters of tradition ») became the transmitters of the Masorah, the tradition of transmission that aims to be faithful to the textual form of the Hebrew Bible, as well as its nuances of pronunciations and vocalizations, practiced in various eras. It was the task of the Masoretes to preserve both the memory of ancient pronunciations and meanings and to unify their practice. ↩︎

- To discover the ancient educational customs of Jewish mothers, I invite you to explore the work of 12David Rouach and notably his book published by Maisonneuve & Larose: ‘imma, or rites and customs and beliefs among Jewish women of North Africa. Likewise, that of Haim Zafrani (Franco- Moroccan historian, research officer at CNRS, born June 10, 1922, in Essaouira and died March 31, 2004, in Paris): Jewish Pedagogy in the Land of Islam, published by Adrien Maisonneuve. ↩︎

- We find accounts « specifying and augmenting » the divine process of creation of the universe as read in the Bible (Genesis) in many texts, notably in the Talmud. In the fundamental texts of Kabbalah, we find this account where God created the entire universe with the letters as they are presented in the Torah. Various works of the Jewish tradition teach that all the letters of the Hebrew alphabet were presented to IHWH and that He chose as the starting point, the second letter, Beith (□), which is the first letter of the first word of the Torah – Bereshit – « In the beginning ». Furthermore, the various combinations of letters (consonants and vowels) in all their permutations manifested to participate in the Creation of the universe (Zohar II, 204a). Thus says the Zohar: « When the Holy One, Blessed be He, created the world, He did so by the secret power of the letters » (Zohar IV, 151b). ↩︎

- The Sefer HaBahir (Book of Clarity) dates from the end of the 12th century of the current era and reinterprets an older treatise, the Sefer Yetsirah (the Book of Creation). Bahir can be translated as « in the Light, » but also as « in Serenity. » This book develops a system of Jewish mysticism based on the very ancient rabbinic notion of Shekhina, conceived as the Divine Immanence of the Ineffable and Holy Name whose inner life would be organized into ten creative powers, the Sefirot listed in the Sefer Yetsirah. ↩︎

- The Masoretic signs (see note 8) that allow for the recognition of the « good » vowels in the biblical texts appear in the form of dots, either circles. ↩︎

- Light of the intellect (’Or ha-Sekhel אוֹר הַשֶּׂכֶל) by Abraham Aboulafia, has been the subject of a magnificent and prestigious publication (2021) by Éditions de l’Éclat, translated and annotated by Michaël Saban in partnership with the Beit Ha-Zohar Institute, with the support of the Foundation for the Memory of the Shoah and the Foundation of French Judaism. ↩︎

- Marcel Jousse (see also note: 1) is the creator of a nomenclature of scientific studies in the pedagogical field: the Anthropology of Gesture. It aims to study the role of gesture and rhythm in the processes of knowledge, memory, and human expression. This science seeks to synthesize various disciplines: psychology, linguistics, ethnology, psychiatry, religious and exegetical sciences, secular and sacred pedagogy… The developments of the Anthropology of Gesture by neuroscience have highlighted the theories of Marcel Jousse, validating cognitive dynamics specific to mystical teachings. ↩︎

- At the forefront of these laws and mechanisms, Jousse places mimism, which is at the origin of all the processes of formation of speech, thought, and logical action in various ethnic environments. Mimism is this specific force of the Anthropos, as mysterious but also as undeniable and irrepressible as hunger or thirst, which causes the child to spontaneously replay the sounds, movements, the « gestures » (this word encompasses, for Jousse, everything that can be recorded by the senses) of their universe. ↩︎

- Henry Corbin, born on April 14, 1903, in Paris and died on October 7, 1978, in the same city, is a 19th philosopher, translator, and French orientalist. ↩︎

- What Jean-Louis Vieillard-Baron, emeritus professor of philosophy at the University of Poitiers, reminds us of: « The events that occur in the imaginal world cannot be understood according to our historical categories; they are manifestations of God, theophanies, in the most beautiful form, that of angels. Henry Corbin spoke of the Angel-Holy Spirit, of the vision of Christ as Christos Angelos: he found here the Neoplatonic tradition. » ↩︎

- In Catholic circles, the major difficulty comes from what is apprehended in Gnostic thought in relation to heresiology. And it is a true marker of the growing difficulty that separates the meaning of the words used in Catholicism on one hand and the academic world on the other. The word « Gnostic » which often qualifies this type of practices is linked, for Catholics, to Manichean deviations and to systems of thought that could be labeled as totalitarian. Historical Jewish Gnostic thought, as understood in the academic circles that have studied it, fundamentally rejects Manichean and dualistic deviations, even if these were inspired by Gnostic elements. The amalgamation of the « Catholic heresiological » vision was again recalled by Pope Francis in April 2018 with much virulence, stating that « …Gnosticism leaves no room for uncertainty and seeks an inner illumination that will make the Gnostic say: I know, and not: I believe. » But what the Pope rightly evokes regarding the essence of his thought is a deviation of the doctrines and practices grouped indiscriminately by heresiologists under the label « Gnostic. » Deviations that can be known by many other spiritual movements, particularly within Catholicism itself. If one remains vigilant to the traditional Judeo-Christian wisdom that invites to frame practices through permanent questioning (critical spirit and search for sources), references to peers (dialectic) and to the fathers (through texts), pride and totalitarian visions can hardly take part in the journey. ↩︎

- The Tserouf is an interpretative method that invites one to permute vowels and consonants of a word or phrase to discover its deep meaning. Practiced in Hebrew culture certainly several centuries BC, this practice is the subject of an impressive literature and mainly produced by the sages of the Kabbalah (Jews and Christians) from the medieval period to the present day. ↩︎